Franco Manni

Razze , razzismo

, traumi culturali, e chiarezza concettuale e ... inconveniens

sulla tolleranza

La razza è sinonimo di sottospecie, se tra una specie e un'altra non c'è interfecondità, essa invece c'è tra una razza (sottospecie) e un'altra come si vede nelle razze equine, canine e anche umane.

Sono evidenti le divisioni in gruppi della umanità in base alla apparenza religiosa (islam buddismo, etc) , rispetto alla nazionalità cioè lingua (francofoni, arabi, anglosassoni, etc.) m,a è anche evidente la loro divisione rispetto a caratteristiche biologiche (neri, asiatici, mulatti, etc.) Queste caratteristiche biologiche sono appunto le sottospecie o razze della nostra specie homo sapiens...

Però a causa della tragedia del nazismo e dell'olocausto, e a causa del razzismo anche successivo e anche attuale, ecco che c'è un trauma morale ed intellettuale nella coscienza Occidentale e questo trauma fa sì che si confonda l'ideologia politica (molto negativa) del razzismo che è un fatto appunto politico, con l'esistenza delle razze, che è solo un fatto biologico.

Razzismo significa credere che una razza sia superiore alle altre e che a causa di questa presunta superiorità possa permettersi di levare alle altre diritti e al limite perseguitarle.

Razza significa che un insieme di individui posso esser raggruppati tra loro per somiglianze somatiche che li accomunano tra loro più che con altra individui.

Quali caratteristiche? Non sono quelle degli organi interni tipo pancreas o composizione del sangue etc, ma quelle esterne, visibili, che colpiscono a prima vista: come colore della pelle, forma del naso, glabrità o pelosità della pelle etc.

Coloro che - assurdamente - negano l'esistenza delle razze ( e dunque di queste differenti caratteristiche di raggruppamento ), certamente non riusciranno mai a convincere la gente comune ai cui occhi tali differenze sono evidenti e non scompariranno mai. Ma commettono il grave errore sia intellettuale sia morale di dare questo messaggio alla gente: per affermare che tutti gli uomini hanno eguale dignità e dunque devono avere eguali diritti, bisogna affermare che essi siano eguali nelle loro situazioni materiali e di fatto...

… ma questo è un grave errore, perchè la eguale dignità deve essere riconosciuta non se siamo eguali (tutti cristiani, tutti eterosessuali, tutti sani , tutti fascisti, tutti dello stesso gruppo biologico)!!!. essa uguale dignità deve essere riconosciuta proprio quando vediamo che materialmente , economicamente, linguisticamente per opinione politica, per fede religiosa, per caratteristiche somatiche, per orientamento sessuale NOI SIAMO DIVERSI. Uguale dignità morale e giuridica, nonostante le differenze materiali e sociali!!!

Altrimenti sparisce lo stesso concetto di tolleranza. Infatti è assurdo dire che si esercita la virtù della tolleranza verso chi è uguale a te per religione, classe sociale, nazionalità etc , essa la si esercita proprio0 verso chi è diverso da te!

Se proprio non si vuole urtare la malata ipersensibilità di queste persone snob che negano l'esistenza delle razze, si usi pure un altra parola (gruppi biologici, sottospecie, classi genetiche … che so!)... però è un errore intellettuale e morale negare la realtà!

Allego due documenti sulle esistenza delle razze, entrambi molto autorevoli:

1)

il primo è la voce "human races" dal CD 1997 della Encyclopedia

Britannica, cioè la migliore enciclopedia del mondo;

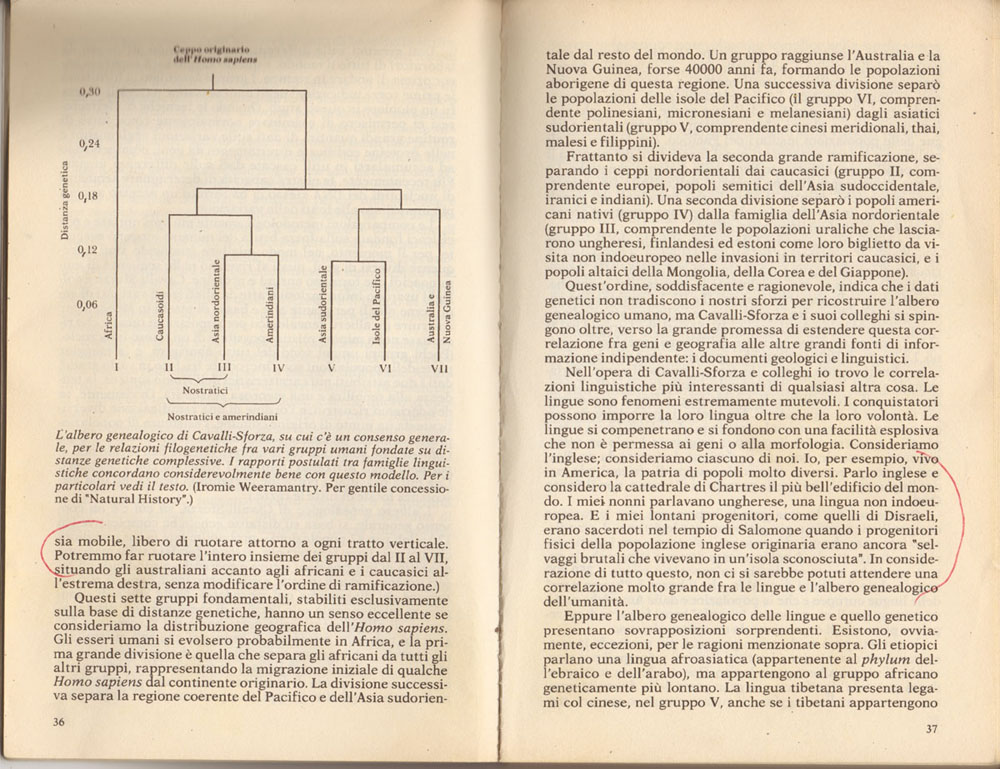

2) l'altro è una scannerizzazione della parte del libro di S. J. Gould

(professore di biologia ad Harvard e probabilmente il più grande studioso

di Darwin del XX secolo) che cita uno studio di Luca Cavalli Sforza

(probabilmente uno dei più importanti genetisti viventi) e riproduce un

suo diagramma che distingue i sottogruppi biologici della nostra specie

umana (le razze umane!) secondo la quantità di cromosomi differenti.

© Encyclopedia Britannica – 1997

GENETICS OF RACES AND SPECIES DIFFERENCES

Arthur

Robinson, M.D. Professor of

Biochemistry, Biophysics, and Genetics and of Pediatrics, University of

Colorado, Denver. Senior staff member, National Jewish Center for Immunology

and Respiratory Medicine, Denver.

Francisco

Jose Ayala. Donald Bren Professor of

Biological Sciences, University of California, Irvine. Author

of Evolving: The Theory and Processes of Organic Evolution and others.

Russell

Howard Tuttle. Professor of

Anthropology, University of Chicago. Author of Apes of the World: Their

Social Behavior, Communication, Mentality and Ecology.

The

nature and origin of R A C E S

and species are dealt with in

the article EVOLUTION, THE THEORY OF, particularly in the section

Species and speciation. Here it is necessary to consider only the genetic

composition of the R A C E and species differences in sexually

reproducing and outbreeding organisms.

In

general, species are considered to be populations of organisms between

which breeding is impossible or significantly limited under natural

conditions. Subgroups of an individual species with distinctive

phenotypes form R A C E S, members of which can interbreed with members of other

R A C E S of that species. The geneticist Curt Stern defined a R A C E as a

group more or less isolated geographically or culturally who share a

common gene pool and who, statistically, are somewhat different at some loci

from other populations.

In

naturally occurring populations a species may split into R A C E S because

of a gradual geographical separation and eventual rift between formerly

interbreeding groups. Such R A C E S, which inhabit different territories,

are called allopatric. If these R

A C E S are brought together, they assume a

sympatric status, interbreed, exchange genes, and fuse into a single

genetically variable population. R A C E S of human beings and of

certain parasites are exceptional because they can coexist, at least for a time,

sympatrically. In humans, social rather than geographical or biological

factors slow down interbreeding and R A C E fusion. Distinct species

may, on the other hand, be either allopatric or sympatric. The exchange of

genes between species populations is prevented not only by geographic

distance (as with R A C E S) but also by genetically based reproductive

isolating mechanisms. Reproductive

isolation is achieved by a variety of means: differences in preferred

habitats, in breeding seasons, in sexual attraction and courtship rites,

in sexual structures (flowers in plants and genitalia in animals);

incompatibility of sex cells; inviability of the hybrid progenies;

sterility of the hybrids; and weakness of the gene recombination products of

the gene complements of the species.

R A C E differences are more often quantitative than qualitative; racially distinct populations of a species differ usually in the frequency of certain genes rather than the presence or absence of certain genes.

Studies

on human blood groups have revealed

some instructive situations. As discussed earlier, the four "classical"

blood groups O, A, B, and AB are due to three alleles of a gene. Most

human populations have individuals of all four types, and even parents and

children, as well as brothers and sisters, may belong to different

blood groups. However, some blood groups, and hence the gene alleles that

produce them, are more frequent in some countries than in others. The

gene for A blood, for example, increases in frequency from east to west

in Europe; B blood is most frequent in some populations of India, Tibet,

Mongolia, and Siberia. A majority of American Indians apparently had,

before the arrival of Europeans and Africans, the O blood group only;

however, the tribes of the Blackfoot

and Bloods had the highest known frequencies of A blood, which is also very

frequent among the Lapps in northern Europe (see also BLOOD: Blood

groups). Human R A C E S differ certainly in many genetic

traits, not in blood groups alone. Some theorists, imagining the human population

as it might have been about 4000 BC, have speculated that there were perhaps

five major R A C E S, one for each inhabited major landmass.

The

major human R A C E S are separated by their most readily recognized

characteristics, such as skin colour, body size, and facial morphology.

In modern times many of the barriers, both geographic and cultural, between the

R A C E S have weakened.

Since most of the external differences between R A C E S are polygenically

and environmentally determined, interracial matings produce offspring

that, in general, have a phenotype intermediate between those of the parents.

Of the total number of loci existing in the human

species, numbering at least 100,000, the majority of their alleles probably

are present among the members of each R A C E.

Although

one population of alleles--for example, those for dark skin colour--may be

common in one R A C E and rare in another, each particular skin-colour

allele occurs in both R A C E S. In fact, studies involving many

polymorphic loci (loci with two or more alleles occurring with a frequency

of at least 1 percent) have revealed that the allelic diversity among

individuals within a single R A C E is greater than that between R A C E S.

Intelligence is a highly variable characteristic that some have

claimed varies among different human R A C E S. This characteristic is

difficult to define and even more difficult to measure. In addition, it is

significantly influenced by environmental factors. Finally, the trait

certainly varies more within members of a R A C E than between R A C E S. R

A C E S are genetically open systems, and gene exchange between R A C E S

does take place. Species, by contrast, are genetically closed systems

in which gene exchange is rare or absent. R A C E differentiation is

reversible; hybridization or intermarriage may cause R A C E S to merge

into a single population. It is an error to think that in a population

resulting from R A C E hybridization all individuals will be alike; in point of

fact, such hybrid populations show a remarkable diversity of individuals.

Species differentiation is irreversible.

R

A C E S are populations, and an individual may have a genetic endowment that

can occur in two or more different R A C E S or that is not common in

any R A C E. An individual belongs, however, to only one species, unless

that individual is a species hybrid.

Mules, hybrids between the horse and donkey, are sterile because of

abnormalities in the processes of sex-cell formation in their gonads.

Sterility of hybrids between species, if viable hybrids between them

can be obtained at all, is observed very frequently, though some

experimentally obtained species hybrids have proved to be fertile. Scientists

have asked what causes the development of the gene-frequency differences

between populations that live in different territories, or, in other

words, what makes these populations racially distinct.

The probable explanation is that genetic differences

between populations arise in most cases through natural selection in

response to the local environments that prevail in the territories they

inhabit. It is, however, very difficult to verify this explanation in many

concrete instances of R A C E differentiation. For example, it is

probable that the dark skin pigmentation of many human populations that

live, or have until recently lived, in tropical and subtropical

countries protects them from sunburns. It is probable also that the light

skin colours of the natives of Europe facilitate the acquisition of

vitamin D in regions with deficient sunshine.

The

evidence for even these hypotheses is not as conclusive as might be

desired. But when it comes to such racial traits as hair form and shapes of

the nose, of the lips, and of the cheekbones, no acceptable evidence of

adaptive significance is available. The situation is no better with R A

C E S of animals and plants: for most racial differences the adaptive

significance is unknown. Attempts have been made to envisage

factors other than natural selection that could be responsible for genetic

differentiation of populations. Appeals are frequently made to

pleiotropism of the gene action; a visible R A C E difference may in itself

be neither adaptive nor unadaptive, yet it may be only an outward sign

of an underlying physiological difference that is adaptively important.

An elegant example is the coloration of onions--red and purple bulbs are

resistant to the attacks of a smudge fungus, while white bulbs are

highly susceptible. A R A C E trait may also be important as a sexual

recognition mark, or it may play a role in the courtship ritual. A

most interesting possibility that should be seriously considered is that

some differences between populations may be due to random

genetic drift. As was discussed above, genetic drift acts on small

populations. Suppose that a species lives in many

isolated colonies, some of them consisting of only tens or perhaps

hundreds of individuals. Chance events may cause the gene frequencies

in the different colonies to drift apart. How important this random genetic

drift may be in R A C E differentiation is controversial. That genetic

drift does occur is certain; a simple example is that in small villages a

sizable fraction of the inhabitants sometimes have the same surname,

and different surnames are frequent in different villages. Increasing

or decreasing frequencies of the surnames evidently go together with

increases or decreases of the frequencies of certain genes that the

ancestors of the people with these surnames carried. As discussed, genetic

drift can also arise from the founder effect. When the populations of

new colonies founded by a small number of individuals expand, they will be

found to differ genetically from each other and from the ancestral

population. Natural selection will then come into operation, giving rise to

new balanced gene pools. The founder

effect was probably important in the development of some human populations.

Many tribes and local R A C E S may be the descendants of small numbers of

original migrants and settlers. Whether the random genetic drift alone

can explain the origin of the gene complexes that differentiate R A C E S or

species is very doubtful. The point is, however, that genetic drift and

natural selection are not mutually exclusive alternatives; it is not one or

the other but the interaction of both that brings about R A C E

differentiation. The founder effect is a special case of random genetic

drift. The gene pool of a colony derived from a single immigrant or

several pairs of immigrants may need a restructuring by natural selection

to become properly adapted to the new environment.

Human

Evolution R A C E AND POPULATION Definitions and

terminology.

The

term R A C E as applied to humans has been variously used--by politicians,

military leaders, philologists, human biologists, demographers, and

historians. Some "R A C E

S" constitute language groups, often of peoples whose only kinship is

that they speak a common language. Such was the original meaning of the

so-called Aryan R A C E. Some "R A C E S"

are simply hypothetical, invented to embrace present distributions of

such genetic (hereditary) characteristics as stature or hair colour--e.g.,

the Nordics. (The word Nordic also has been given a political meaning,

referring, despite their differences in physical characteristics, to

peoples in northern Europe.)

R

A C E has been variously applied to national or cultural groupings, as in

the days when English writers referred to an Irish R A C E and to a

Scottish R A C E. As used in census and other applications, the designation R A C E

often groups different peoples for administrative convenience; thus, the

category Hispanic may group people from Meso-America, the Caribbean,

South America, and the Philippines who may differ considerably in their

racial origins. "R A C E" also has been applied to

human groups inferred to have existed on the basis of archaeological

discoveries; the Etruscan R A C E is an example. Various religious

groups who may or may not have common ancestry sometimes are called R A

C E S--the Jewish R A C E, for example. By extension of biblical thinking

and in honour of Shem, son of Noah, a Semitic R

A C E was conceived in an effort to describe peoples who spoke Semitic

tongues, some of whom may have learned their language more recently

than others.

All

of those uses of the term R A C E are separate and distinct from its

biological meaning in classification (taxonomy)--the natural

divisions or groupings below the species level. As such, R A C E differs from breed or line,

which refer to artificially established groups maintained by intensive

selection or by deliberate hybridization. Just as the term R A C E is often

too broadly applied to the entire species of man (as in the human R A C

E), particular R A C E names invented to explain distributions of observable

physical characteristics of human populations are not biologically

meaningful.

The

misuse of the word R A C E--particularly the manner in which it was employed

by Nazi Germany--had led workers to search for alternate terms. Some

biological descriptions refer to human stocks, one intention for this

being to avoid political overtones. Other writers have favoured the

word division in lieu of R A C E, again apparently to escape what may be

perceived as offensive connotations. Other references to these human

groupings include strain (without implying the equivalent of purebred strains

of laboratory animals); variety (although the specific botanical

meaning does not apply to human R A C E S as ordinarily constituted);

and ethnic group, which, although generally meaning cultural or

political groupings (e.g., Macedonians, Croats, Magyars, or Slovenes),

is at times used with exactly the same biological meaning as R A C E.

With

the advent of population genetics, establishing gene frequencies in

specific populations, many

workers have come to prefer the word population for taxonomic

purposes. Populations so defined, however--such as San (Bushman), Ainu, Lapp,

Eskimo, Coloured (South Africa), or Micronesian--are often the same

groupings that have been or can be called R A C E S. Still, population is a

useful addition for such linguistically and genetically distinct groups

as the Basques and is an easier concept to explain.

The

term geographic, or continental, R A C E is often used to describe

populations that occupy a broad geographic range. Likewise, local R A C

E is used for populations in a more restricted area, and microR A C E may

correspond to a single, extended breeding population. These natural

groupings, which reflect geographic (and therefore reproductive) isolation,

display a range of genetic differences that are the focus of much

research. The ultimate questions are how long the R A C E S (or populations)

have been distinguishable and what processes brought about the

distinctions. What the different geographic R A C E S are called

is to some extent unimportant as long as the same terminology is employed by all;

such traditional designations as white, yellow, and black, however, are

clearly inappropriate. The designations for local R A C E S and microR

A C E S are similarly unimportant, except for communication and for the

sensitivities of the people themselves. It has long been a practice on

the part of some human taxonomists to convert place-names into taxonomic

names by adding the suffix -id (e.g., Pennsylvanid, Montanid) or the

suffix -oid (Capoid for the Cape peoples of South Africa). Geographic terms, without

suffixes, also suffice (hence, the Mediterranean R A C E) or are used in

conjunction with language groupings, where justified (e.g.,

Azteco-Tanoan). Often reference is made to particular national or cultural

groupings, such as Finns, because available data are so arranged, or to

artificial groupings (e.g., Ghanaians or Vietnamese) until further

information can establish more precisely the makeup of those groups.

Even a designation as being from a city may not be enough, given demographic and

genetic differentiation within cities, Tokyo being a typical example.

Human

Evolution Geographic R A C E S.

Naturally occurring (i.e., produced by natural,

usually geographic separation

of human groups) R A C E S of the human species are by no means

identical in number of members or degree of genetic differentiation. There

are small groupings of a few hundred to a few thousand individuals,

some slightly and only recently isolated reproductively from adjacent

people. Other equally small groups may have been mating apart from the

rest of mankind for centuries or even for thousands of years. Members

of some human R A C E S number in the hundreds of millions (as the peoples

of modern Europe) or in the billions (as in Asia).

It

is both useful and meaningful to identify the very large human groupings

that often correspond to continents or other major geographic areas as

geographic R A C E S, a term extensively used with other life forms.

Geographic R A C E S are numerically large, containing within them

smaller groups of reproductive isolates (breeding populations). The reasons

for the large groups' geographic delineation are usually clear. The

Indians of the Americas were

reproductively separated from the peoples of other geographic regions

for many thousands of years. Thus, they have come to differ genetically from

the rest of mankind and even from those Asians from whom they stemmed.

The Australian Aborigines

similarly constitute a geographically defined group of local R A C E S

(see below) separated for millennia from the rest of the world, except for

some slight contact, until the late 18th century. Human

Evolution The antiquity of Homo sapiens. It is a

curious fact that, although evidence for the evolution of man is extensive,

direct fossil evidence of the earliest members of the species Homo

sapiens is relatively scarce. The species H. sapiens (of which the modern

human R A C E S comprise a number of different geographic varieties)

may be defined in terms of the anatomic characters shared by its members.

The definition for prehistoric representatives of the species must be

limited to skeletal characters, the only remains to be found, and includes

such features as a mean cranial capacity of about 1,350 cubic centimetres

(82 cubic inches), an approximately vertical forehead, a rounded

occipital (back) part of the skull with a relatively small area for the

attachment of the neck musculature, jaws and teeth of reduced size,

small canine teeth of spatulate form, the presence of a pointed or

projecting chin, and limb bones adapted to a fully erect posture and

gait. Any skeletal remains that conform to this pattern to an extent that

precludes classification in other groups of higher primates must be

assumed to belong to anatomically modern H. sapiens. In the past there

was a tendency to create entirely new species of Homo on the basis of

fragments of prehistoric human skeletons, even though the remains

showed no significant differences from modern man. This tendency was

prompted by the supposed antiquity of the remains or by a failure to

realize how variable some features are even in modern man. The species of

the genus Homo that immediately preceded H. sapiens was H. erectus, and

it is most likely that sapient humans (H. sapiens) evolved from H.

erectus.

Franco Manni indice degli scritti

Maurilio Lovatti main list of online papers