Maurilio Lovatti

Emilio Gabaglio and the ACLI (Christian Associations of Italian Workers)

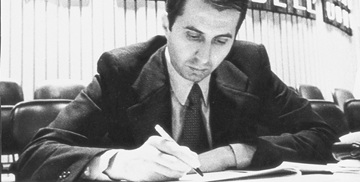

Emilio Gabaglio was elected president of the ACLI by the National Council on July 6, 1969, with a large majority (69 votes out of 84), when he was only 32 years old. The vice-presidents were Geo Brenna, Maria Fortunato, and Marino Carboni.

Gabaglio, born in 1937, originally from the ACLI in Como, and with a degree in economics from the Catholic University, arrived in Rome in 1962, when Livio Labor was national president, to head the ACLI social affairs research office. In December 1963, he became head of the international affairs office. After the 1966 congress, he joined the national presidency and two years later became secretary, following the resignation of Vittorio Pozzar, who was running for the Senate for the DC (Democrazia Cristiana Party).

On September 17, 1969, Cardinal Giovanni Urbani died following a serious illness, and on October 3, Cardinal Antonio Poma, Archbishop of Bologna, was appointed President of the CEI (Italian Episcopal Conference) by Pope Paul VI. During the Turin Congress and for the remaining months of 1969, the CEI abstained from any official intervention on the ACLI, to the point that Cardinal Poma, when he received President Gabaglio and Central Assistant Msgr. Cesare Pagani in early December, did not raise any issues. However, from Emilio Gabaglio's correspondence, we know that in the fall of 1969, Msgr. Santo Quadri, Auxiliary Bishop of Pinerolo (Turin) and former Central Assistant, had twice visited the ACLI national headquarters to meet with the presidency, on October 27 and November 19, 1969. Although unofficially, as the CEI's expert on social issues, Quadri had intervened to exchange views on the definition of the presence of assistants following the ACLI's increased political commitment after the Turin Congress. In reality, Quadri had almost subjected the new presidency to a thorough examination, requesting clarifications and details on the congressional decisions. In preparation for the second meeting, he wrote to Gabaglio: "[ACLI's] commitment to questionable timing regarding humanization accentuates the need to reconsider the position of the priest and the structure of ACLI's contribution to the pastoral care of the world of work." (Letter of November 6, 1969).

On January 15, 1970, Gabaglio was received in audience by Pope Paul VI. According to Gabaglio's own statement to the ACLI Executive Committee, the discussion focused on issues related to the "Christian identity of the ACLI," and the Pope desired a clarifying dialogue with the CEI on this matter. Gabaglio stated that he was "personally very comforted" by the discussion and added that "the Pope has expressed a lively and ongoing interest in the ACLI." He concluded optimistically by stating that "if the ACLI implements the choices it has made, it need have no worries whatsoever." (Minutes of the Executive Committee, February 11, 1970). As soon as he left the audience, Gabaglio expressed his feelings and revealed that he felt comforted by the outcome of the meeting. The news was first reported by Panorama and then by various newspapers, suggesting that the Pope had endorsed the decisions of the Turin Congress, which the ACLI president had outlined during the audience. After informing the presidency, Gabaglio wrote to the Pope, having been prompted to do so by "the persistence of a certain press in exploiting the meeting that You so kindly granted me a few days ago, to the point of almost involving Your Holiness in matters of political and other contingent considerations." He expressed his "sincere regret at such insensitive behavior of which, albeit unwittingly, I was the occasion." (Letter of February 2, 1970).

On behalf of the Pope, Msgr. Giovanni Benelli, Substitute of the Vatican Secretariat of State, responded: "The Holy Father instructs me to express his gratitude for your kind gesture, with which you have filially resolved an episode that has caused me considerable distress." On this occasion, Benelli thanked Gabaglio for his "kind visit to the Secretariat of State," and added some considerations that clearly frame the nature of the confrontation between the ACLI and the Hierarchy that would develop in the coming months:

"I believe we must sincerely question whether the current policies expressed by the ACLI in the political and trade union arenas, as well as the methods and initiatives through which it intends to implement its social commitment, correspond to the true nature and original characteristics of a Movement that arose for the training of workers and the social advancement of the working classes, laborers, and farmers. We must openly ask ourselves whether the Movement's Christian inspiration is truly operating as a primary purpose and as a Christian witness and inspiration in the world of work, in which the ACLI operates and of which it is a part. You well know the Holy Father's great affection for the world of labor, which occupies a preeminent place in the teaching and pastoral care of his Pontificate; you know how much trust he has placed and places in the ACLI's ability to be an effective instrument for the Christian advancement of the working classes: this, in fact, is how the Hierarchy conceived those Associations, implemented them, and supported them throughout their twenty-five years of historical experience. I believe it is necessary to clarify to the ACLI members themselves and to the entire Italian ecclesial community whether the Movement intends to remain faithful to these statutory and fundamental tasks, in order to continue to deserve the same trust and support from the Church." (Letter from Msgr. Giovanni Benelli, February 19, 1970).

On March 6, 1970, Gabaglio was summoned to the CEI headquarters, then still on Via della Conciliazione, where Archbishop Andrea Pangrazio, secretary of the Italian Episcopal Conference, in the presence of Archbishop Franco Costa, president of the Commission for the Laity and central assistant of AC (Azione Cattolica), officially presented him with a lengthy letter from Archbishop Antonio Poma, president of the CEI, which made detailed requests to the ACLI for clarification, to be provided with "urgency" out of a "duty of loyalty to its members and the entire ecclesial community."

Gabaglio recounts:

"After reading the contents of the envelope, the basis for organizing a dialogue, as the Pope had mentioned, immediately seemed far from being established. For this reason, I had a small disagreement with Monsignor [Pangrazio], to whom I told that the Pope had spoken of organizing a dialogue, while the letter, which I was asked to read immediately, did not seem to point in that direction." (E. Gabaglio, From Turin to Cagliari the ACLI continue, speech at the round table Pope Paul VI and the crisis of the ACLI in 1971, at the National Study Conference Verso la democrazia associativa, Vallombrosa, 31 August 2001, in A. Scarpitti, Le ACLI e la Chiesa, Aesse, Rome 2002, pp. 28-32, at p. 29).

In the preface of the letter, Poma clearly sets out the reasons that led the Bishops to intervene decisively:

"You are well aware of the perplexity the Association's recent orientations have raised among Bishops, the clergy, the Catholic laity, and public opinion regarding ACLI's fidelity to the statutory duties from which it derives its structure, which justifies its presence and activity. Indeed, the Hierarchy itself - which has always been concerned not to disrupt the movement's struggle, respecting its autonomous and responsible choices - is now continually called into question, as if it shared the new orientations and supported certain experiments. On the other hand, it cannot be denied that deep divisions are emerging among the national and local leaders - widely felt by public opinion as well - with differing and, at times, conflicting assessments, which even touch upon the Movement's very inspiration. (Letter from Msgr. Antonio Poma, March 2, 1970).

The four questions posed by the CEI can be summarized as follows:

1. Are the ACLI's activities still based on the "doctrine of Christianity according to the teaching of the Church"?

2. Do the original purposes of the ACLI, as set out in Article 2 of the Statute (educational, training, social security, cooperative, and recreational), still define the Movement's activities?

3. Do the ACLI still intend to avail themselves of the presence of [priests] assistants, tasked with ensuring that "the Associations' activities are carried out in harmony with the principles of Christian morality and the directives of the Church"?

4. Is the method that the ACLI "appears to wish to follow for the change of society" still consistent with the teaching "contained in the ecclesiastical, pontifical, and conciliar magisterium"?

In explaining point no. 2, Cardinal Poma does not hide what the Bishops' primary concern is:

"At this point, I cannot fail to raise a serious concern being expressed by many, a concern that we Bishops, indebted to all, cannot ignore. Many fear a dangerous confusion could arise between the ACLI - despite their statutory autonomy - and new groups, not overtly partisan, but nonetheless decidedly political. In this regard, the fear that the ACLI's asserted autonomy in the political sphere, in addition to weakening the still free but shared civic commitment of Catholics, will in fact directly benefit forces whose subversive, authoritarian, and destructive tendencies toward the essential values of the person cannot guarantee the true social advancement of the working class."

Poma's letter did not arise from a specific need explicitly expressed by the Bishops, although it reflects widespread concerns among the prelates, but was directly requested by Pope Paul VI. Cardinal Jean-Marie Villot, Vatican Secretary of State, had written to Poma: "The Holy Father believes that, faced with this situation, it is appropriate for Your Eminence […] to address a written document to the President of the ACLI to request specific clarification" (Letter from Cardinal Villot to Cardinal Poma, February 20, 1970, cited in A. Riccardi, La Conferenza Episcopale Italiana negli anni Cinquanta e Sessanta, in G. Alberigo, Chiese italiane e Concilio: esperienze pastorali nella chiesa italiana tra Pio XII e Paolo VI, Marietti, Genova 1988, p. 58), also attaching a memorandum that essentially indicates the specific contents of the note to be forwarded to the ACLI. On February 26, the CEI Presidential Council, instructing Cardinal Poma to write to Gabaglio, had conducted a "careful examination" of the ACLI issue.

Gabaglio promptly informed the provincial associations of the ACLI, copying Poma's letter (March 9, 1970). However, the ACLI leaders involved in the tormented debate with the episcopate ignored Pope Paul VI's personal intervention and tended to explain the bishops' attitude as responding to a predominantly political need. Gabaglio writes that after the Turin congress, "there was a very decisive reaction from the DC secretariat, which immediately turned to the CEI, but in practice to the Vatican, to ultimately request a call to order of the ACLI." (Interview with Emilio Gabaglio, in C. F. Casula, Le ACLI. Una bella storia italiana, Anicia, Rome 2008, p. 31). Gabaglio also refers to a letter that "Flaminio Piccoli, the secretary of the DC, sent to the Secretariat of State," going so far as to point out that "the DC continued to fan the flames and use every incident as a pretext." Vice President Maria Fortunato expressed a similar assessment: "We later learned that the national secretariat of the DC at the time had repeatedly appealed to the hierarchy to silence the ACLI because the decisions taken at the Turin congress no longer made the ACLI a collateral movement to the DC, and they feared the end of Catholic political unity, which had historically served as a defense against communism." (Interview with Maria Fortunato, in AA. VV., Una lunga fedeltà. Per una storia religiosa delle ACLI, Coop. Ed. Nuova Stampa, Milan 1995, p. 68).

The ACLI Executive Committee of March 14, 1970, approved a "memorandum," a very long document that constitutes the essential reference for Gabaglio's response to Poma's letter. From the outset, it reaffirms the consistency of the movement's current orientations with its history: "the ACLI has always denounced the capitalist structures prevalent in Italian society as unjust"; and explains the "particular emphasis in recent years" as the natural result of their experience in the world of work. The guidelines of the Turin congress are firmly defended: "for the ACLI, being Christian and being a worker today entails […] a class choice, embodying their Christian witness, both individually and as a group. In this sense, class choice means siding with workers, the oppressed, and the exploited..."

In particular, the fundamental choices of the Turin congress are defended and explained, such as "the end of any practice of collateralism – without exception – towards any party or other formation operating in the strictly political-partisan sphere, with the implementation of the incompatibilities provided for by the statute" and "the adoption of the principle of personal, free, and responsible voting by ACLI members […] This entails, among other things, that the ACLI, for its part, will not give electoral recommendations of any kind, nor will it present its own lists or ACLI candidates, as has happened in the past." Unlike the Bishops, the ACLI believe that "the existence of differentiated and questionable choices on a social level cannot and must not disturb ecclesial communion."

The document concludes by recalling that "the Assistant is, in the ACLI, wanted, desired and honoured in the fullness of his priestly function" and that "already today the priest is not implicated in the questionable choices of the ACLI and is not invoked to support them", however the ACLI is manifested as willing "to experiment with hypotheses of a different type from those foreseen [… by] the statute, without prejudice to the presence and priestly contribution of the assistant." (14 March 1970).

The minutes of the meeting, which summarize the debate, referencing the meetings of the provincial presidencies with their respective bishops, state: "The Bishops demonstrated their unawareness of Cardinal Poma's letter, including those who are members of the CEI Presidential Council. More than one Bishop expressed some doubts and even disagreement regarding the tone and content of the letter."

Obviously, ACLI leaders could not have learned of Paul VI's intervention through Cardinal Villot, yet their meetings with the bishops of the various provinces seem to confirm that Poma's letter did not arise from unanimous demands expressed by the bishops. Also significant are the interventions of Msgr. Pagani, who offers a very reassuring and optimistic interpretation of the proposed meeting with the CEI and appears to be staunchly defending the ACLI's decisions. In reporting the outcome of the meeting with the peripheral assistants summoned to Rome in the preceding days, he states that the assistants themselves "recognized the opportunity to provide a more precise theological foundation for Turin's decisions; they welcomed this episode as a providential opportunity to more firmly engage our Bishops in a truly substantive dialogue" and also believe "they must facilitate the dialogue […] by helping the Bishops themselves accept the experimental method and urging them to provide more priests to the ACLI." With one inevitable reservation: "After the assistants have done everything possible to make clear what is truly within the ongoing process […] and after they have clearly and honestly stated their thoughts and positions, they must ultimately consider the value of obedience." Archbishop Pagani concludes by acknowledging "the great responsibility and significant testimony with which the CE [ACLI Executive Committee] is managing the situation."

At the

request of Poma himself, whom he met on March 13 in Bologna, who requested a

prompt response to his letter so he could report to the plenary assembly of

bishops, Gabaglio sent a response letter to the president of the CEI on

March 18, without waiting for the ACLI National Council, which was convened

on March 21-22, 1970. Gabaglio, after stating that the ACLI "willingly

adheres to the desire for clarity underlying these questions," affirmed

that the ACLI did not intend to renounce its "Christian character,"

that the autonomy of the ACLI movement could not "be detrimental to the

affirmation of Christian values," that the ACLI did not intend to

renounce its assistants and "at most could suggest the opportunity to

examine further pastorally appropriate forms" of their function.

Finally, the president denies that collaboration with left-wing forces in

the labor movement could undermine the Christian inspiration of the ACLI and

hopes that the "entire content of the memorandum," that is, the EC

document, forwarded with the letter, can be "better clarified and

documented in the meetings for which Your Eminence expresses his full

availability." Overall, the letter appears softer in tone than the EC

document and also more specific in addressing the questions posed, as well

as being much shorter.

First Disagreements

At the ACLI National Council on March 21-22, the first significant internal rift occurred regarding the attitude to be taken in relations with Church authorities. The CE document was approved by a large majority (48 votes out of 57 present), while the minority countered with an alternative document, proposed by Enzo Auteri of Catania, spokesperson for the minority led by Giovanni Bersani, and signed by 11 other national councilors. This document stated that it was not enough to reaffirm the ACLI's fidelity to Christian inspiration, but rather it was necessary to eliminate "statements, attitudes, and behaviors" that might raise doubts or misunderstandings in this regard. Furthermore, ACLI leaders must "clearly separate their responsibilities before public opinion" in the face of behavior by ACLI leaders that could be interpreted as "attempts at new collateral choices that were neither authorized nor consistent with the congressional resolutions, and that could lead, through a policy of fait accompli, to neo-frontist solutions." With a disillusioned realism, Auteri himself states: "It's pointless to argue because the answer to Poma has already been given, reiterating the decisions made in Turin, which the hierarchy has already rejected." The minority believes it represents the feelings of the majority of ACLI members, and in fact Bruno Olini maintains that "the hierarchy's concerns coincide with those of the majority of members."

Dialogue with the Italian Episcopal Conference

Amidst a climate of great uncertainty about the outcome, on May 12, 1970, the first clarification meeting took place at the CEI headquarters. It lasted approximately three hours, with a "mutual exposition of points of view" between the CEI delegation, led by Enrico Nicodemo, Archbishop of Bari and Vice President of the CEI, with Bishops Franco Costa and Santo Quadri and Bishop Pietro Pavan as an expert, and the ACLI delegation, composed of President Gabaglio, Vice Presidents Geo Brenna and Maria Fortunato, and Bishop Pagani. Emilio Gabaglio recalls that the protagonists of this first meeting were Geo Brenna and Bishop Quadri, who meticulously discussed theological issues and interpretations of the Church's social doctrine. During this discussion, Bishop Nicodemo whispered to Gabaglio and asked: "Listen, this whole discussion is fine, but how are you going to vote in the regional elections?" (interview with Emilio Gabaglio, in Le ACLI e la Chiesa, p. 30). Gabaglio's impression is that at that moment the episcopate's fears were more political than doctrinal or pastoral. Maria Fortunato also recalls: "Monsignor Nicodemo, Archbishop of Bari and president of the bishops' delegation, entered the room and patted me on the shoulder and said: 'Miss Fortunato, let's be clear; we know you are good Christians and we have no doubt about this, but the problem is another. It's political. Who do you vote for? And who do you make people vote for?' This was the question, very clearly posed by the bishops." (M. Fortunato, An Ideal Socialism, in A. Scarpitti, C. F. Casula, The Socialist Hypothesis Thirty Years Later (1970-2000), Aesse, Rome 2001, p. 37). However, Msgr. Pagani expressed a more than reassuring assessment of the outcome of the meeting, saying he was "very impressed by the meeting and underscored the positive nature of a dialogue […] well underway. On our part, there was an intuition of the Bishops' true pastoral concerns; on the Bishops' part, there was greater awareness that things are much more complicated than they have traditionally considered" (Minutes of the CE of 23 and 24 May 1970).

The second meeting is scheduled for after the summer, a clear sign that the discussion could have taken place without pressing deadlines and in a calm manner. Complicating the situation is the ACLI national conference being held in Vallombrosa (Florence) at the end of August and, above all, the intense coverage of its outcomes in the national press.

National Meeting in Vallombrosa

Between August 27 and 30, 1970, nearly 500 ACLI leaders and executives attended the 18th ACLI national study meeting in Vallombrosa, entitled "Workers' Movement, Capitalism, Democracy." At the conclusion of the meeting, national president Gabaglio formulated the famous "socialist hypothesis," which sparked heated public debate in the Catholic world and received extraordinary media coverage. Gabaglio's final political presentation followed three presentations featuring highly critical economic and social analyses of the capitalist system: one by Fausto Tortora, head of the ACLI research office, on the organization of business and labor; one by Gabriele Gheradi on the international aspects of capitalist development; and one by Pietro Praderi on social and union struggles in the factory and in society.

Speaking on the final day, drawing on previous presentations, which, despite their language heavily influenced by the then-widespread Marxist culture, were presented as contributions to the analysis and study of society, Gabaglio draws a series of political conclusions for the ACLI. According to the president, since the Turin congress, the ACLI movement has fully realized that "the productive and socializing potential that advanced societies are capable of developing must no longer be used to perpetuate the domination of narrow elites through the subordination and exploitation of the working class, but must be placed at the service of the personal and collective fulfillment and promotion of man as a person and of the community of all men."

For Gabaglio, if one agrees with the thesis that "there is no real democracy if working citizens are deprived of the fundamental right tied to the concrete overcoming of alienation and discrimination: the right to effectively participate in determining the destination of the fruits of social labor," then very specific indications emerge regarding the essential features of the alternative social model to capitalism that the ACLI intends to propose. First, regarding the right to property, Gabaglio states that it was a deliberate choice of the Second Vatican Council to avoid to reiterate that the right to property is a natural right; in fact, the "truly natural right is not the right to ownership, to the possession of property, to the possession of goods, but rather the right to the participation of all in the dominion of goods. This goal, in the form of private ownership of the means of production, has not historically been achieved and does not appear attainable for all, not even for a majority of them, but only for a few." The ACLI president expresses a strongly negative opinion of "industrialized socialist" countries (such as the USSR), which have abolished private ownership of the means of production, and openly criticizes state ownership of businesses because it "continues to perpetuate the alienation of workers from the means of their labor, excluding them from decisions regarding production, the distribution of wealth produced, and the general organization of the economy and society. Furthermore, the issue of the division of labor, borrowed from capitalist modes of production, which ultimately gives rise to a veritable social stratification, remains unresolved." The abolition of private ownership of the means of production is therefore a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for building a society aimed "at man rather than at profit," without forgetting that "socialist-type structures alone are not enough to build a society of man for man." Gabaglio's presentation is characterized by a strongly utopian tone and prophetic tension as he outlines the features of the alternative society to capitalism, which the ACLI intends to work towards:

"It is not enough to eliminate intensive exploitation, the reduction of labor to a commodity. We must consider business as the place and moment in which people can realize themselves through work, understood as the expansion of their creative capacities in the service of the community, overturning the values and behaviors that derive from the capitalist organization of labor. […] We must promote a radically different project, according to which people organize their personal and community existence, according to values that are certainly not pre-established, but which can and must already be said to tend to replace the atomization of individual competition with relationships of solidarity and brotherhood."

Based on these analyses, the ACLI's commitment must be characterized by an "anti-capitalist choice, authentically oriented toward human development, and therefore not excluding the socialist option." For Gabaglio, this option is compatible with Christian conscience and requires a "counter-project" for change grounded in class consciousness. The president concludes his long and detailed report by stating that the ACLI's anti-capitalist choice is "irreversible" and that there is a need "to deepen our research for a different future for humanity, without excluding the authentically socialist option." Although formally, the reports at the annual national study meetings were given in a personal capacity, it is undeniable that Gabaglio's expresses the views of the ACLI leadership. Also interesting and enlightening is the testimony of Franco Passuello, who confirms that Gabaglio's report was certainly not the result of improvisation:

"Together with Angelo Gennari […] I worked for two months on the Gabaglio report. […] Emilio was in Como and […] took our draft, halved it, reworked it, and what turned out to be the final text was examined line by line, chosen, and evaluated by him […] When Angelo and I reread the entire report in one go […] we looked at each other and said: 'Mamma mia, the end of the world is happening here.'" (F. Passuello, Nel contesto internazionale, in L'ipotesi socialista, p. 41.).

Domenico Rosati also confirms that Gabaglio's theses expressed the majority opinion of the ACLI leadership group and recalls that, in a quick meeting prior to Gabaglio's response, the leadership group had collectively endorsed the president's political proposal:

"Gabaglio's text […] had been made known to the members of the presidency only immediately before its reading, while a central team worked on its development […] for months. It was quickly decided to authorize the president to commit the leadership group to the report's line. 'We ask,' they said, 'to be judged on that proposal.'" (D. Rosati, A History Not Yet Complete, speech at the round table of the XVIII National Study Meeting in Vallombrosa, in L'ipotesi socialista, pp. 51-52.)

The minority that had formed at the Turin congress voiced its criticism of Gabaglio's theses, already during the debate on the final day of the conference. The minority that had formed at the Turin congress the previous year, led by Christian Democrats Giovanni Bersani, Carlo Borrini, Michelangelo Dell'Armellina, Vittorino Colombo, and Enzo Auteri, had begun organizing as an internal component at the local level since February 1970 in Veneto, Bologna, Puglia, Rome, and the other few provincial areas where it could count on some local leaders. It only began to raise the prospect of a split after Vallombrosa, with the well-founded hope that the socialist option, deemed incompatible with the moderate orientation of most ACLI members, would further aggravate the hierarchy's discontent with ACLI leaders.

More complex to decipher are the reasons that led former president Livio Labor to receive Gabaglio's arguments with coldness and perplexity. Labor, present at Vallombrosa as a mere ACLI member with no management responsibilities, intervened on August 29 (the day before Gabaglio's speech) in the debate on the Italian political situation that followed Praderi's speech, but remained conspicuously silent in the debate on the national president's speech. Labor, questioning the role of Catholic workers in the current political landscape, stated: "Our response cannot, must not, and never will be resignation to the existing balance of power and democracy, resignation to a supposedly 'fatal' encounter between this DC (Christian Democracy Party) - moderate, conservative, resigned, and mocking any effort at political-democratic creativity - and this PCI (Italian Communist Party) […] resigned and sometimes itself hostile to any attempt at creative renewal in the methods of organizing and managing class-based political forces." The former central president also presents his political proposal, namely "a workers' political movement, autonomous and autonomist, secular, committed to the progress and liberation of man and to a new internationalism.

To understand why Labor, whose charisma among ACLI members was still very much alive, preferred to insist on the inadequacy of existing political forces in confronting the ongoing moderate and conservative offensive, while remaining silent on the socialist hypothesis, it is necessary to keep in mind that a few weeks earlier, the ACPol (Political Culture Association) had officially dissolved (July 4) and a constituent phase had been envisaged for a new left-wing party, the Movimento Politico del Lavoratori (MPL), promoted by the same elements that had founded the ACPol: the socialist left led by Riccardo Lombardi, the New Forces led by Donat-Cattin and Bodrato, CISL trade unionists, and Catholics of ACLI origin led by Labor. The constituent phase began a few months later, with the Sorrento conference on November 20-22, 1970. The intention to found a new party, and also its reasonable prospects of success, were linked to the fact that, between the final months of 1969 and the spring of 1970, Donat-Cattin, Bodrato and the leadership group of Forze Nuove, the Lombardi's left of the PSI and the group of CISL trade unionists led by Carniti and Macario, had expressed, even in public forums, their willingness to participate, together with the ACLI members of Labor who had joined the ACPol. In particular, Donat-Cattin, at a current conference in Sorrento in 1967, had stated: "Either we leave the DC within the years that can be counted on the fingers of one hand or we will become notables" (L. Labor, Non l'MPL ha fatto soffrire le Acli, in Scritti e discorsi, vol. 2, pp. 313-338, at p. 331): and then on several unofficial occasions he had supported the inevitability of the split; in particular, two years later, accepting the post of Minister of Labour in the Rumor II government (August 1969), he had revealed to Labor that "he was going into government to better qualify himself politically and thus make his exit from the party more significant." (L. Labor, Non si torna indietro, interview given to A. Barone, in «Alternativa», 7 May 1972).

Yet, just two months before Vallombrosa, on July 6, 1970, Forze Nuove's willingness to leave the DC and participate in the founding of the MPL suddenly faded, at the meeting convened by Gabaglio at the Villa Sciarra Hotel in Monte Porzio Catone (Rome) to define the new party's constituent process. In fact, the political landscape was rapidly evolving: the previous year, Moro had definitively left the Dorotei, toward whose political line he was becoming progressively more critical, had established good relations with left-wing DC factions, and was developing his own plan for collaboration with the PCI. This plan would become more realistic if the DC remained united and the internal left-wing factions were increasingly able to influence its policies. In this political context, Labor's political project, contrary to the optimistic forecasts formulated at the time of the dissolution of the ACPol, risked being compromised even before the MPL's constituent phase could begin. In this situation of weakness, Labor was taken aback by Gabaglio's report. A few years later, speaking about himself in the third person, he explained:

"The word socialist viscerally triggers a reaction within the Italian Catholic world and the Catholic hierarchy. Compared to the achievements of Turin, Vallombrosa '70 was a departure and a provocation; it also rendered Labor's exit from the movement pointless. Labor had repeatedly declared that he was leaving the movement because the socialist choice had to be made on his own account, not on the movement's account. So he wrote to the National Council in December 1969, resigning, and refusing, forever, to become a sort of eminence grise manipulating the ACLI from the outside, as, unfortunately, many, too many, have baselessly imagined and written. What happened in Vallombrosa in August 1970, in my opinion, blocked the process of peaceful internal political differentiation, which we had foreseen and desired, with sincere respect for that majority of ACLI workers who still vote DC, of which we were fully aware".

Labor's position is ultimately clear: it does not disagree on the merits of Vallombrosa's theses, but considers them "a naive political error, which has drawn the Catholic hierarchy onto the ACLI (certainly not for the first time!), forced the leaders into two years of bitter meetings and clashes, and subsequently prompted the painful condemnation of the Pope, accompanied by a manipulated split." (L. Labor, Non l'MPL ha fatto soffrire le Acli, pp. 315-16).

For Labor, the socialist choice could legitimately be made by individual ACLI militants, but it should not involve the movement as such. Furthermore, the real risk was that Gabaglio's positions would appear to the outside world to be inspired or dictated by Labor itself, which had designated Gabaglio as its successor as national president, and would raise suspicions of the ACLI being exploited for the benefit of the nascent MPL.

Gabaglio himself confirms: "As I have written on several occasions, Labor had no part in the affair. In public he called the socialist hypothesis 'a naive mistake,' but face-to-face he did not spare me more severe criticism. First of all, because of the inner suffering that the worsening ACLI crisis, which had already begun in Turin, caused him, and secondly, because of the well-founded belief that our difficulties would certainly not make the path of his new political experience easier." (Letter from Emilio Gabaglio to Luigi Bobba, dated June 25, 2001, in L'ipotesi socialista, p. 71).

The path by which the ACLI arrived at the socialist hypothesis, however, was entirely within the context of a critical analysis of the social needs emerging from the growing awareness of the workers' movement, which had developed through the union and political struggles of the second half of the 1960s. This was interpreted in light of the ACLI's own Christian inspiration. Therefore, it differs significantly from similar, and apparently similar, positions emerging in those same years from Christian grassroots communities (i.e. Comunità di base), primarily for religious reasons. Indeed, the grassroots communities, which were highly participatory at the time, embraced political struggle as a core commitment in their Christian life, interpreting it through interpretations more or less explicitly close to Marxism, with nuances similar to those of the extra-parliamentary left. The vast majority of their members did not intend to abandon their ecclesiastical affiliation; they simply believed that the Gospel message should be interpreted in light of political categories and advocated a reform of the Church based not only on the outcomes of the Second Vatican Council, but also as a result of political practice. The ACLI's socialist hypothesis and the pro-Marxist elaborations of many grassroots communities, due to their origins and motivations, therefore remain distinct and parallel processes, with little mutual influence. Their extrinsic analogies only document the strong hegemony that Marxist culture exercised over the average mentality of political militants at the time, influencing their language and even their understanding of the relationship between theory and practice.

The Vallombrosa Meeting leaves open the question of the compatibility of the socialist hypothesis with the social doctrine of the Church and with the general orientations regarding the Church's presence in the contemporary world defined by the Second Vatican Council. Gabaglio, already at Vallombrosa, and subsequently the national presidency of the ACLI on several occasions, particularly in meetings with the CEI delegation, maintain that the socialist hypothesis, which emerges as a natural necessity from the role assumed by the workers' movement in trade union and social action, is not only fully compatible with the ACLI's Christian inspiration, but also represents a positive development of the Church's traditional commitment to humanizing society in keeping with evangelical values. However, given its political connotations, it remains a questionable option and therefore should not engage or compromise the hierarchy. On the other hand, various bishops and intellectuals in the Catholic world believe that the socialist hypothesis already implies, on a logical and value-based level, the assumption of the thesis of the incorrigibility of capitalism and that it is therefore necessarily destined to enter into a collision course with the social teaching of the Church.

Meanwhile, on August 1, 1970, Poma confirmed Msgr. Cesare Pagani as central assistant of the ACLI for a further three years. Attached to the appointment was a letter, published by the CEI Newsletter, containing binding instructions on the exercise of the office: "The work of the assistant, while respecting the responsibilities inherent in lay people's temporal commitments, must be able to constitute [...] a guarantee of fidelity to the Church, assistance, and coherence between Christian inspiration and concrete choices of action [...] With this commitment, every ACLI assistant [...] will be able to be of great assistance to Christian workers' associations in remaining faithful to their inspiration and their original purposes, thus ensuring their credibility as a work of the Church before the Christian community." (Poma's letter to Pagani, August 1, 1970, prot. 1493/70). In the CEI newsletter, at the bottom of the Secretariat's communication of September 2, which forwarded Poma's letter to the bishops, a particularly significant Nota Bene (be careful) is added ("The aforementioned documents were prepared before the recent ACLI conference in Vallombrosa"), which suggests that the outcomes of Vallombrosa have profoundly changed the climate of dialogue between the CEI and ACLI.

However, Pagani, in the same CEI Newsletter, continues to firmly defend the ACLI's orientation, despite the internal minority's dissociation: "I think I can say with clear conscience that the ACLI represents an essentially positive Christian experience. […] For the Catholic world, they constitute a scandal for some, but also a hope for others." He also expresses substantial support for the orientations of Turin and Vallombrosa, even if expressed in more cautious language, for example, when he reiterates that the ACLI's purpose goes beyond the formative stage and is "the construction of an earthly city of a radically and necessarily evangelical dimension".

The Resumption of Dialogue with the Italian Episcopal Conference

Only in

November did the series of meetings between the CEI and ACLI delegations

resume, but the bishops' attitude and tone was more resolute than in the May

meeting. The meeting on the morning of November 9th was preliminary in

nature; Gabaglio and Pagani were present for the ACLI, while Bishops Nicodemo

and Quadri were present for the CEI. On the afternoon of November 9th,

Nicodemo and Quadri received two representatives of the ACLI minority (Auteri

and Borrini) at the Domus Marie.

The bishops' assembly from November 9th to 14th discussed the ACLI case, and

in an interlocutory context, doubts were raised about the nature and

function of the ACLI. However, there were interventions entirely favorable

to the Christian workers' movement, such as that of Bishop Luigi Liverzani:

"The ACLI's crisis is due to the fact that they, more than any other

association operating in the sector, have become aware of the situation, and

this is a positive fact. […] It is therefore necessary to support the ACLI

so that they can carry out this service from an ecclesial perspective."

(Minutes of the CEI General Assembly, 9-14 November 1970, in Proceedings

of the VII General Assembly, Edition reserved for Bishops, CEI, Rome

1970, p. 192).

The final statement does not appear to conceal a marked hardening of convictions, where the bishops: "express the conviction that the discussions already begun with the ACLI leaders, and now made more urgent by recent doctrinal and programmatic orientations, must be continued and promptly concluded, with the clear assumption of their respective responsibilities." Surprisingly, the ACLI president interprets the orientation of the CEI plenary assembly by denying any hardening: "The tone and atmosphere appear to have been very positive, and the conclusion is extremely valid, also due to the bishops' increased awareness that, with regard to issues that involve judgments of merit and assessments of appropriateness, one must scientifically equip oneself with appropriate tools."

Subsequent meetings took place on December 9 and 10, 1970, and January 8 and February 1, 1971. The previous CEI delegation was joined by the Archbishop of Syracuse, Giuseppe Bonfiglioli; the Bishop of Frascati, Luigi Liverzani; the Auxiliary Bishop of Bologna, Luigi Dardani; and, as an expert, the Jesuit Father Bartolomeo Sorge, director of La Civiltà Cattolica. Archbishop Costa was still formally part of the delegation, but no longer participated in the meetings. The ACLI delegation, however, remained unchanged at all meetings (Gabaglio, Brenna, Fortunato, and Pagani). In the first meeting, the CEI delegation listened to and acknowledged Gabaglio and Brenna's clarifications on: the condemnation of capitalism, the Marxist analysis of society, private property, the socialization of the means of production, self-management, participation, and revolution. Among other things, Gabaglio states: "we are […] revolutionaries, but for a revolution that is not based on violence, but on conviction." (Minutes of the CEI-ACLI meeting of 9 December 1970).

Geo Brenna is a staunch and unequivocal critic of the Catholic party: "A political party like the DC, which today positions itself as a supporter of the neocapitalist system rather than a means of changing it, despite being sociologically interclass, has in practice made a choice contrary to ours. Parties should be judged by the policies they actually implement, not by their programs..."

And Gabaglio doubles down: "The DC […] betrays its ancient values […] We don't exclude the entire DC, especially the DC left, from our range of interlocutors, but we often don't find them with us, alongside the workers." Regarding the relationship between the ACLI and the hierarchy, Gabaglio specifies that "we have always taken care not to involve the Hierarchy in our questionable decisions" and states: "We feel the need for an increasingly vital relationship with the Hierarchy. However, we seem to be in the position of those who shy away from two extremes: that of a "mandate" relationship and that of a "judgment" relationship […] In our opinion, the ACLI are positioned in a "consensus" relationship."

At the conclusion of the meeting, Msgr. Pagani insisted on his role as an aspiring mediator: "Today, in the ACLI, engaging in politics is about seeking a grassroots counterpower, and this helps people grow and requires formation in values; therefore, it does not preclude the formative moment, which is what ultimately concerns the Church."

After this initial meeting, Monsignor Cesare Pagani, in a confidential letter to Gabaglio and Brenna, expressed his disagreement with certain aspects of the arguments put forward by ACLI leaders in their meeting with the bishops. After noting that "you know that I have personal reservations about the ACLI's current decisions," and in order for the doctrinal clarification requested by the bishops to be effective, he believed that "precise and unmistakable facts are urgently needed that demonstrate the ACLI's originality and, therefore, credibility. […] I ask you to ingeniously and courageously develop concrete proposals that demonstrate, with facts, the clear distinction from extremist protest groups […] from Marxism and Marxist forces; the clear division from the MPL (Workers' Political Movement) (as is emerging today); […] a clear hypothesis regarding the forms of presence and action of the Priest in the Movement." (Letter from Pagani to Gabaglio and Brenna, January 1, 1971).

A few weeks later, before attending an audience with Paul VI, the ACLI Assistant wrote again to Gabaglio to confirm that the "discomfort I felt" regarding the ACLI's guidelines was neither "psychological nor subjective": "I ask you to take this into account, as you know well, to overcome the real difficulties of this moment, to courageously initiate some revisions." (Letter from Pagani to Gabaglio, January 31, 1971).

At the meeting of January 8, 1971, the bishops expressed their initial assessments of the clarifications provided by ACLI leaders at the previous meeting. For example, on the thorny issue of the natural right to property and the legitimacy of limiting it to promote the overall good of society, the bishops reiterated that "the Church's social doctrine on private property as a natural means of guaranteeing personal expansion seems sufficient to them to protect the common good and ensure the participation of broader segments of the population in governance and power." Referring to Vallombrosa's socialist hypothesis, the bishops argued that theses expressed in Marxist language must be preceded by "a clear clarification of those fundamental principles that the ACLI, as a Christian movement, cannot but accept." (Minutes of the CEI-ACLI meeting of January 8, 1971).

The meeting concluded with the ACLI delegation confirming that "the movement's political choice is irreversible: the ACLI can never again become an ecclesial workers' movement, as it was 20 years ago." The bishops responded that "it is therefore necessary to review the relationship between the hierarchy and the ACLI," and the ACLI confirmed their willingness to "revise the statute on this point." During the last meeting, on February 1, 1971, Bishop Nicodemo stated that, in his opinion, "the possibility of the bishops' disavowal of the ACLI is excluded," and Father Sorge added that a judgment by the bishops "that sounded like a disavowal would be a historic error." (Personal notes by Emilio Gabaglio).

Reconstructions and assessments of the entire series of discussions between the CEI and ACLI delegations are quite heterogeneous. According to Gabaglio, who briefed the ACLI Executive Committee, "the Bishops' assessment of the progress of the dialogue is to be considered positive; Archbishop Nicodemo was keen to clarify that the bishops do not consider themselves a judging panel; that their availability is complete," but "doctrinal doubts" remain regarding private property, the methods used to analyze society, and the compatibility of class struggle with charity and collaboration with left-wing forces. Many years later, Gabaglio himself expressed a much less optimistic assessment: "I have always had the impression that some of the participants in the discussion wanted to help better understand and clarify, while other interlocutors had this desire to a lesser extent [...] Vallombrosa objectively radicalized the problem. If there were already questions about the choices made in Turin, which were in some ways politically neutral, the so-called socialist hypothesis was immediately interpreted as a choice of sides and not as research, albeit questionable, of a cultural nature or aimed at measuring oneself against new things. Despite this, the dialogue continued, but could not be concluded." (Gabaglio's speech at the round table Paolo VI e la crisi delle ACLI nel 1971).

In the Summary Note of the opinions expressed by the ACLI delegation in its meetings with the CEI, Gabaglio informed the Executive Committee that the ACLI had further clarified the content of the socialist hypothesis that emerged at Vallombrosa. Specifically regarding private ownership of the means of production, the ACLI believed it was right for the state to place "limits on the right of individuals to property" and to expropriate private property that "hindered the common good." The ACLI also urged the bishops to pursue the "socialization and self-management" of the means of production (excluding nationalization) and "binding democratic planning." The ACLI further clarified to the bishops that they believed "the criterion of profit and that of productive expansion as an end in itself should be abandoned as absolute criteria; the guiding principle must be the satisfaction of the real needs of the community." They reiterated to the bishops that "class struggle is a fact and not a means; for the ACLI, it is never an end." Regarding the movement's relationship with the hierarchy, according to the ACLI, "it should be expressed through a consensus of the Hierarchy, in accordance with the teaching of the Council, not on the individual choices or activities of the ACLI, but on the legitimacy and validity of their declaration as a group of Christians who, in addition to a specific social commitment to the workers' movement, wish to develop and nurture their witness as a community."

Another key figure in the ACLI-CEI discussions, Maria Fortunato, recalls significant aspects: "We divided the tasks this way: Gabaglio asked Brenna to be the 'tough guy', to be the most inflexible, while he played the mediator: he was the president, and it was right that it should be his. Of the three of us, I was the one who knew the Catholic world best, and I tried to demonstrate that the ACLI acted this way precisely because they were Christian. […] I was the most pessimistic of the three, in assessing the possible outcomes. They said: 'They're listening to us.' But I said: 'Emilio, they're listening to us, but they don't accept a word we say.' They accuse us of giving too much importance to the economy. […] They listened to us, but they continued to think we had gone beyond what they considered acceptable." (Interview with M. Fortunato, in S. De Fazi, Maria Fortunato, Aesse, Rome 2000, p. 21).

As for the CEI delegation's point of view, the only one to have gone beyond the strict confidentiality and the limits of officialdom was Father Bartolomeo Sorge, Secretary who recorded the meetings and a consultant to the bishops: "I was impressed by the way these meetings went: it was a veritable bombardment of questions and answers, like an exam. The questions covered all the theses of Marxism, but the answers the ACLI members gave were not in contradiction with the social doctrine of the Church; if anything, theirs was an attempt at a 'baptized' rereading of Marxist terminology and theses; in short, it was the first attempt at 'inculturation' of what we can consider the dominant culture at the time." (Speech by Father Bartolomeo Sorge at the round table Paolo VI e la crisi delle ACLI nel 1971, August 31, 2001, pp. 33-38, at p. 33). On February 8, a week after the last meeting, the CEI Presidential Council made public its dissatisfaction with the outcome of the meetings for the first time: "The requests presented by the Committee [of bishops] gave rise to explanatory responses, which, even with the most benevolent interpretation, given the choices made by the movement, were not enough to dispel the doubts and reservations of a doctrinal and especially pastoral nature that had given rise to the dialogue." (Communication of the CEI Presidential Council of February 8, 1971).

In the summary of the report of the Bishops' Committee, entitled Guidelines for an Evaluation of the Situation of the ACLI, also published in the CEI Newsletter (1971, Supplement No. 1, pp. 32-35), the doctrinal doubts concerning the socialist hypothesis are reiterated, such as the abolition of private ownership of the means of production and the class struggle. However, it is on the pastoral aspect that the criticisms are strongest and most cutting: "The easy extremism and fanaticism that derives from the socialist hypothesis, as understood by workers, can generate temptations to violence [… and] there is also the danger, despite the ACLI's wishes to the contrary, of being exploited by the PCI, compromising the values of civil and religious freedom." ACLI's political commitment has also been explicitly criticized, as it "effectively holds the hierarchy accountable to public opinion in a sector that is not its own (ACLI effectively carries out all the activities carried out by political parties, excluding, for now, only the presentation of their own electoral lists and the direct assumption of political power)."

Faced with this development, Msgr. Cesare Pagani no longer hides his concerns: "The bishops seem to be expressing a negative judgment, or at least a lack of confidence, that could lead to a disavowal of the ACLI. If this were the case, it would be a historic mistake. Doctrinally, there are no fundamental conflicting elements; regarding social choices, it is right to refer to the realm of opinion, even if doubts may arise regarding practical behavior. It is up to the laity, as such, to make their own decisions freely." (EC Minutes, February 11, 1971). And again, summarizing the bishops' concerns, Pagani states that "Msgr. Nicodemo attempted to demonstrate that the doctrinal doubts were not illogical, but consciously logical. The Bishops have emphasized the pedagogical aspect closely connected to the ACLI's behavior, with its inevitable repercussions on workers as well as on the Catholic world." From the CEI press release, he feels "we can say that the verdict on the ACLI is almost definitive." He doesn't shy away from evaluating his own role in the affair: he feels "excluded from the game by the will of the Bishops because they consider him weak and inadequate [...] The assistants have pursued the line of mediation between the leaders: Bishops and lay people. This line has failed."

This perception of the failure of Pagani's mission is also confirmed by Msgr. Giuseppe Pasini, a historian of the early ACLI and deputy central assistant from 1967 to 1971, who experienced the affair firsthand as a member of the group of national assistants. He states, in fact, that Msgr. Cesare Pagani "had been explicitly called to Rome by Pope Paul VI to 'save the movement' from possible deviations, and enjoyed the Pope's sympathy and trust until the end. At a certain point, however, the negative judgment we know prevailed in the Holy See: he, in particular, was attributed primary responsibility for the failure to save the ACLI." (Interview with Msgr. Giuseppe Pasini, in Le ACLI e la Chiesa, p. 50). A very similar judgment is also that of Msgr. Quadri, who highlights a further aspect, relating to the difficulty of communicating directly with the Pontiff: "Even Msgr. Pagani, although a close friend of Montini, was no longer able to speak with him." (Interview with Monsignor Santo Quadri, in A. Scarpitti, Santo Quadri, Aesse, Rome 2000, p. 34).

Despite Pagani's pessimism, which would prove justified in light of subsequent decisions, there was still much uncertainty among the bishops regarding the proper approach to the ACLI. At the meeting of the Episcopal Commission for the Laity on March 9 and 10, 1971, Msgr. Liverzani admitted that the ACLI, during meetings with the CEI delegation, had formulated "historical and existential judgments that cannot be challenged on a doctrinal level" and that "they appeal to Marxism only for the analysis of society, but they affirm the value of the human person." (Minutes of the CEI Commission for the Laity, March 9-10, 1971, no. protocol 1340 of May 26, 1971). And Msgr. Bonfiglioli states that the competence of ACLI members in political choices must be recognized, even if it is evident that on a pastoral level they can create difficulties and misunderstandings, but in any case "a position of the CEI should not be a disavowal." (ibid., p. 28). In a more extensive memorandum delivered to the commission members, Msgr. Costa expressed a decidedly pessimistic outlook: "It is believed that there is little hope for the discussions initiated between Bishops and ACLI experts and leaders. The ACLI does not intend to make its decisions with the Bishops, but only among themselves, within their bodies. Since the discussions began, following the Vallombrosa conference, the situation has become much more serious." (Annex No. 3 to the Minutes of the CEI Commission for the Laity, March 9-10, 1971).

Meanwhile, in the days immediately following the Executive Committee meeting of February 11, 1971, Pagani organized several meetings with the local assistants to assess the situation. These meetings were held without the presence of ACLI leaders, prompting a formal protest from Gabaglio, who wrote to him, "At a time when we are attempting to establish a new type of relationship between leaders and priest-assistants, and in the face of such a weighty problem, it seems to us that the path we are following contradicts this different working perspective. Rather than creating the conditions for greater interpenetration, it reveals a certain detachment, breaking with established practice." (Letter from Gabaglio to Pagani, February 17, 1971, ref. 34/71). The president also expressed the national presidency's discomfort with the interpretations resulting from the exclusion of the leaders from these meetings, and feared that "this will fuel shadows that certainly do not benefit a commitment that we have considered and consider common." Msgr. Pagani responded immediately: "I do not deny that the loyalty and friendship you refer to should have discouraged the drafting of the letter itself." After recalling that meetings of assistants without leaders have often occurred in the past, he maintains that an exchange of ideas "limited to priests" is more fruitful because "the CEI's latest positions directly and seriously affect our priestly mission in the ACLI." (Letter from Pagani to Gabaglio, February 22, 1971).

In any case, the national assistant's concerns regarding the bishops' orientation are more than justified; in fact, at the conclusion of the CEI Presidential Council of May 4-6, 1971, a declaration on the social teaching of the Church was issued, in which several paragraphs are dedicated to the ACLI:

"The Italian episcopate has had to take note of some choices, recently made by the ACLI in their full autonomy, regarding both conceptual and programmatic approaches, as well as a deliberate political line with the resulting forms and collaborations. On the other hand, political, trade union, and economic commitment, even if seriously inspired by fundamental Christian values and aimed at authentic testimony, in its concrete temporal choices is the task of Christians as citizens, not of the Church as such, or of an association operating within it; and therefore the Hierarchy, while respecting every legitimate freedom, cannot and must not be compromised by questionable temporal options. […] It has been noted in particular that the choices made in recent times by the ACLI have given rise to considerable difficulties and disturbances within and outside the Associations themselves, and have created many pastorally difficult situations that are incompatible with a harmonious unitary vision of the ecclesial community. Therefore, in respect of the autonomy claimed by the ACLI and their free choice to be only a movement of Christian workers, the Bishops do not they believe that today the ACLI are among those associations for which the Apostolicam actuositatem decree requires the consent of the Hierarchy (n. 24)."

The bishops' reference is to the third paragraph of Chapter 24 of the conciliar decree on the apostolate of the laity: "Indeed, the lay apostolate admits of different types of relationships with the hierarchy in accordance with the various forms and objects of this apostolate. For in the Church there are many apostolic undertakings which are established by the free choice of the laity and regulated by their prudent judgment. The mission of the Church can be better accomplished in certain circumstances by undertakings of this kind, and therefore they are frequently praised or recommended by the hierarchy. No project, however, may claim the name Catholic unless it has obtained the consent of the lawful Church authority". Taken literally, therefore, the bishops' pronouncement is not a repudiation of the ACLI, and many bishops, in particular, interpret it this way. Indeed, from a historical perspective, it is the first time that the conciliar principle of the responsibility and autonomy of the laity in political decisions has been formally and authoritatively applied to the Italian situation. Among the dozens of statements from residential bishops, the most significant and authoritative in decisively denying any hypothesis of disavowal are those of the bishops of Turin, Novara, and Brescia.

Cardinal Michele Pellegrino, Archbishop of Turin, states: "The CEI's decision in no way signifies the Episcopate's disapproval or disinterest in the ACLI, but merely recognition of their temporal autonomy [...] while it remains clear that the commitment to the Christian formation of workers and the evangelical animation of the world of work is a grave and urgent duty of the Christian community, which must be carried out with the responsibility of all, priests and laity, under the guidance of the Hierarchy, which feels obliged to continue to assist the ACLI to this end, primarily through the work of the priest." (Statement by Cardinal Michele Pellegrino, in "Avvenire," May 13, 1971).

Bishop Placido Cambiaghi of Novara has expressed a similar view. The bishop of Brescia, where the ACLI are particularly widespread and present in social life and the church, is equally supportive of the ACLI. Msgr. Luigi Morstabilini, on May 15, 1971, emphasizing the 80th anniversary of Rerum Novarum: "The Presidential Council of the CEI, while noting that the decisions made recently by the ACLI have given rise to considerable difficulties, has in no way intended to disavow them. […] It has merely separated the direct responsibility of the hierarchy from that of the lay people who, through their free initiative and without passively awaiting instructions and directives, have as their specific task to imbue the mentality, customs, laws, and structures of their community of life with a Christian spirit. […] In other words, the Church has recognized the ACLI as having a more marked autonomy in their temporal choices in the social, political, and trade union fields. With this recognition, it implicitly places its trust in them and recognizes their maturity to operate responsibly in the aforementioned fields." (Statement by Msgr. Luigi Morstabilini, published under the title The Bishop and the ACLI. Trust in Christian Workers and Fidelity to the Teachings of the Church, in "La Voce del Popolo," May 22, 1971).

Even Archbishop Cesare Pagani, in an interview on state television, publicly endorsed these expressions of support from some bishops for the ACLI: "The Hierarchy, with the ACLI - according to a vision that was congenial in the 1940s (sic), when the ACLI was founded - also aimed specifically at pastoral action. Today the Hierarchy claims this exquisitely pastoral action more internally and leaves the ACLI to act specifically in the social, temporal, and political fields, with a Christian inspiration." (Television interview with Archbishop Cesare Pagani in the "Domenica ore 12" program, May 16, 1971).

These benevolent interpretations of the CEI statement are considered "unauthentic" by much of the public and the conservative press.

Although the socialist hypothesis is not explicitly mentioned in the reasons for the bishops' withdrawal of their consent, the crucial importance of the conclusions of the Vallombrosa study conference is undeniable. From this perspective, the most authoritative intervention is that of Cardinal Albino Luciani, who, in May 1971 ("For the ACLI, a turning point imposed by the times," in "Avvenire," May 19, 1971), appeared critical of the ACLI, accusing them of having made "the choice of socialism," a vision that implied "the acceptance of the Marxist analysis of society; the rigid division of men into exploiters and exploited; the denial of private ownership even of medium and small-scale means of production." Domenico Rosati specifies that, in 1978, a few months before being elected Pope, Cardinal Luciani revealed to him that this intervention in Avvenire had been explicitly requested by the Substitute, Msgr. Benelli, "to correct a judgment by Cardinal Pellegrino who denied that there had been a disavowal of the ACLI" (D. Rosati, Il laico esperimento, Edup, Rome 2006, pp. 150-51) and that the bishops had decided to withdraw their consent also influenced by the opinion of Msgr. Quadri, who had stated that the majority of ACLI members were inclined to vote for the PCI.

On the other hand, Gabaglio and much of the ACLI national leadership do not entirely agree with the benevolent interpretation of the CEI statement, albeit with several notable distinctions. The ACLI president opened the Executive Committee by arguing that "the CEI has given more than we asked for. The document reveals a lack of consensus in legal terms […] The Bishops' decision is correct […] in terms of conciliar logic. […] According to this vision, we can be pleased with this step forward. […] The Hierarchy, with this declaration, has precluded itself and any possibility of rebuilding consensus. […] We are today reduced to the 'lay state.' Our Christianity, however, will not cease to be witnessed to, as we are called to do and capable of doing."

Concluding the debate, the national president, while admitting that the positive aspects of the CEI declaration must also be "evaluated," did not hide the potential negative impact of the bishops' stance on the ACLI: "We are faced with a new reality that affects not only the ACLI, but the entire post-Vatican II Italian Church; we are evaluating whether it is appropriate to address [...] an appeal to the grassroots [...] We must move forward. A declaration from the Bishops is certainly not enough to destroy a movement." In essence, Gabaglio welcomes the withdrawal of consent in principle, but does not hide the fact that, in the specific historical and political situation, it constitutes an offensive and a criticism of the ACLI's progressive political orientation.

At the end of the long and passionate discussion, the ACLI Executive Committee approved a document, which was published prominently in Azione Sociale, with the somewhat provocative, capital-letter title, The ACLI Continue. The document, referring to the CEI declaration, states:

"This decision must be considered essentially an element of clarification and distinction of responsibilities. On the one hand, it protects the Episcopate from any compromise, even apparent, with questionable concrete choices—social, trade union, and political—and on the other, it intends to apply the Conciliar Doctrine of the autonomy and competence of the laity in the temporal order. This fundamental distinction of levels and competences, while excluding any possibility of disavowing questionable choices, also prevents any fundamentalist exploitation of the Church's teaching. […] The forms change, but the substance remains unchanged. The Christian inspiration is beyond question: it will continue to illuminate and support the ACLI's autonomous contribution to the workers' movement's struggles for freedom and justice". (May 16, 1971)

The ACLI National Council of June 5 and 6, 1971, confirms this position, and indeed Gabaglio's report suggests a sense of greater relief and tranquility regarding the consequences of the bishops' decision on the future of the ACLI, which appear almost diminished: "The nature of the ACLI, its very essence, its raison d'être, would have been called into question if the ACLI had enjoyed an explicit "mandate" from the Hierarchy in the past. This has never happened and there is no trace of it in the Statute. Or if the CEI had called into question the Christian inspiration of the ACLI. Instead, it is quite the opposite: this Christian inspiration is the subject of the Bishops' declaration of lively and confident hope for the future as well. There is therefore no void, no emergency situation, as if we were facing extreme evils, and therefore remedies were needed. The broad, convinced reaction of the periphery demonstrates the opposite. The Executive Committee was right in stating that The ACLI continue. The ACLI continue because neither their fundamental inspiration nor their historical role nor their ideal and organizational continuity are in question." (Minutes of the National Council of 5-6 June 1971, report of the National President to the National Council).

The belief that the situation caused by the assistants' withdrawal was not dramatic and that the relationship with the group of priests who were former central assistants could substantially continue with the appropriate formal adjustments also emerged from the national presidency meeting a few days later: "to allow the five priests to continue their work with the national ACLI, 50% of the sum foreseen in the budget will be allocated for the second half of 1971 […] Gabaglio will address the problem of the offices with the priests themselves." (11 June 1971).

The Deploration of Pope Paul VI

The Pope's personal intervention completely changes the situation and the tone of the interpretative debate on the CEI declaration of May 6. This is how Pope Paul VI addressed the bishops on June 19, 1971:

"We have witnessed with regret the recent tragedy of the ACLI: that is, we deplored, while leaving it completely free, the ACLI leadership's desire to change the Movement's statutory commitment and political character, even choosing a socialist line, with its questionable and dangerous doctrinal and social implications. The Movement (i. e. the ACLI), which for many years in Italy enjoyed particular interest from the Church, has unfortunately thus, on its own initiative, withdrawn from the sphere of associations for which the Hierarchy grants its "consent." We share your hope that, even in the present situation, the ACLI will remember the origin and purpose for which it was established, and will not deviate from conformity with the principles professed by the Magisterium of the Church in the area of social orientation.

Even just reading the headlines of the following day's newspapers (Sunday, June 20), the meaning of Paul VI's speech seems indisputable: the Pope "deplores" the ACLI (for Il Giorno and Paese Sera), "disavows" them (for Il Messaggero), "condemns" them (for L'Unità and Il Tempo).

Authoritative figures in the Italian Church are no longer using a soft tone. Archbishop Pangrazio, secretary of the CEI, declared: "The Pope has merely clarified what had been glossed over in the Bishops' declaration and what the ACLI leaders had refused to understand." (G. Zizola, Paul VI deplores the new ACLI line, in Il Giorno, June 20, 1971). And Archbishop Nicodemo, vice president of the CEI, accuses the ACLI of "being directly responsible for the episcopate's pronouncement, which was implemented with great sorrow and certainly not with praise." (M. Politi, The Pope disowns the ACLI's choice, in Il Messaggero, June 20, 1971).

Thirty years later, Msgr. Giuseppe Pasini effectively reconstructs the impact of Paul VI's speech on the ACLI leaders:

"The ACLI's disavowal, both as a matter of fact and for the emphasis with which it was expressed, was traumatic for the movement and for the majority of the Catholic world. It must also be added that the Pope's pronouncement came as a surprise to those familiar with the progress of the discussions between representatives of the ecclesiastical hierarchy and ACLI leaders: after understandable initial difficulties, these discussions were moving toward mutually satisfactory conclusions. Suddenly, orders came from above to suspend the meetings, as important decisions were imminent. It was unclear what events had led to the abrupt breakdown in the ongoing dialogue: the most widespread interpretation at the time focused on strong and sudden pressure on the Vatican from ACLI leaders or assistants who dissented from the official line and aimed at reinforcing the thesis of the movement's leaders' unreliability. In other words, the Church could not trust these people: it had to sever ties and teach them a stern lesson. It is also possible that Paul VI had already personally developed the conviction that he needed to break with the ACLI, due to the choices made in recent years that seemed to be overturning its original structure and inspiration. Malicious and tendentious external information may have weighed on the Pontiff, but the role played by Montini in the "refoundation" of the ACLI should not be forgotten. […] In a certain sense, Paul VI, it is conceivable, felt betrayed by the ACLI's choices of 1970 compared to the project he had conceived for the Movement." (Interview with G. Pasini, in Le ACLI e la Chiesa, pp. 47-48).

It will be possible to fully understand the reasons that led the Pontiff to such a harsh intervention, interpreting the public position taken by the CEI more severely (adding explicit condemnation) only in due course, when the documents relating to Paul VI's pontificate are made available to scholars. However, even in the absence of direct Vatican sources, it is possible to formulate hypotheses that are at least plausible, though not definitive. The most plausible explanation for Paul VI's attitude can only derive from and be organically integrated into the overall vision of the Church and the implementation of the Council by the Pope from Brescia. From this perspective, the interpretation proposed by Msgr. Antonio Acerbi, a distinguished Church historian and former professor at the Catholic University, appears to be the most complete and reliable and has the merit of being compatible with all the evidence already acquired by historians. For Acerbi, Paul VI aimed at a profound renewal of Italian religious life:

"The Pope had long since abandoned the stereotype of Italy as a "Catholic nation" and, by nature and culture, shunned the organizationalism that had been, instead, the strategy of Catholic Action until the Council. […] Traditional religiosity did not guarantee the relationship between the collective conscience and the Christian message. The answer to the problem was to be found in what the Pope himself called the "religious choice," which meant, in a negative sense, abandoning the idea that the risks to the faith of the Italian people came only from outside, from the assault of political forces carrying anti-Christian ideologies, and, therefore, a detachment from the temporal line; and, in a positive sense, the conciliar reorientation of the life of the Christian community". (A. Acerbi, The Italian Church from the Conclusion of the Council to the End of the DC, in La Chiesa e l'Italia, Vita e Pensiero, Milan 2003, p. 457)

From this perspective, the Pope primarily intended, on the one hand, to enhance the Italian Episcopal Conference, in which the entire episcopate could express itself as a collective body responsible for pastoral action, and on the other, to reform Catholic Action, which was no longer responsible, as in the 1950s, for ensuring that the political presence of Catholics would allow for the governance of the state and society with a view to establishing a Christian order. Catholic Action, also considering the Council's overcoming of the traditional idea of a Christian order in society, was to make a "religious choice" and become the primary instrument for involving the laity, through education and apostolate, in the conciliar reform of the Church. From this point of view, the Church's task was no longer to influence the DC's programmatic choices (as had historically occurred, for example, with the 1959 congress), but rather to train well-prepared Catholics who would become its ruling class and to support it in its commitment to coherence through persevering dialogue. Even if thus scaled down, the role of the DC was still essential: "In the DC Paul VI saw the guarantee of certain values, namely those of democracy and a balanced social process; this ensured the stability of that general political framework which for him was a condition, albeit external, but necessary, for the renewal of the Italian Church, indeed in a certain sense, for its very future." (A. Acerbi, Paolo VI. Il Papa che baciò la terra, San Paolo, Cinisello B. (MI) 1997, p. 115).